When considering some of

the largest causes for divides within the United States’ electorate today, many

would look towards race, education, age, and sex. However, one cleavage remains

seldom discussed yet may be the most important in correlating to

increased polarization between America’s two parties. The factor of rural

versus urban electorates has remained a strong sorting mechanism between the

two parties throughout the last century and has only increased in recent years.

Though not much can be done to stop this attributing factor of party polarization,

its effects will continue to have significant consequences for the American electorate

in the coming decades.

The

rural and urban divide in the United States was quite insignificant back at the

time of its inception. Thomas

Jefferson was well-known for his disdain of city life back in 1803 when he wrote

that cities were evil, dirty and possibly monarchist compared to the virtue and

wisdom inherent to an agrarian lifestyle. This penchant for pastoralism was undoubtedly

quite popular during a period when 94 percent of the US population was located in rural areas.

However, by 1920 a majority of the US population for the first time was considered as living in

urban areas, causing discourse to change with examples like journalists

describing Republican President Warren G. Harding giving speeches to “small

town yokels … low political serfs.” (Grier 2018). Rural and urban divides have

only increased in today’s political climate and have exacerbated unequal

representation within the national government due to using a system that

attempts to balance rural and urban interests even at the cost of “penalizing the

party with the more concentrated base of support.”

It is

well known in contemporary politics that “urban areas tend to vote Democratic,

while suburban and rural areas often lean Republican” and is known as the geographic

constituency for a member of Congress (Adler, Jenkins, and Shipan pg. 82 2019).

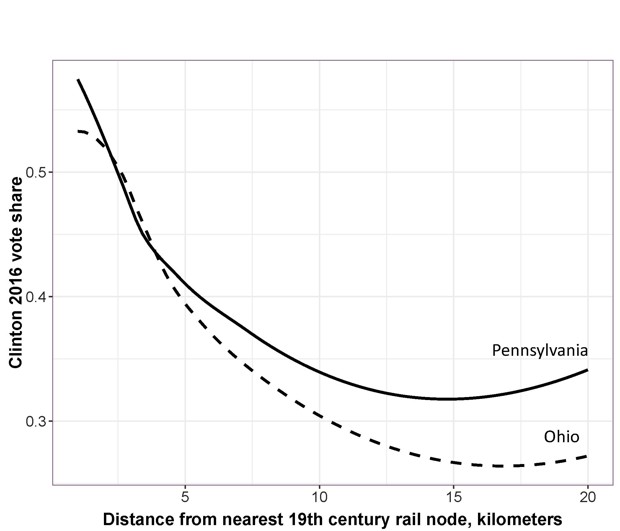

These geographic constituencies may go back centuries, as seen in Figure 1

below, which shows the correlation between the distance of old railroad junctions

during industrialization in the 19th Century and Hillary Clinton’s

vote share in the 2016 election. The farther away a voter is from these rail

nodes, the less likely overall they are to have voted for the Democratic presidential

candidate in 2016.

This correlation also has large impacts on which

candidates are chosen in these districts as well as their representation. Due to

Democrats living in ultra-homogenous politically affiliated districts compared to less solid but more

numerous Republican-leaning districts, America’s winner-take-all district system

leads to “the more concentrated party losing out on transforming votes to seats”

(Florida 2019). Another consequence of this is that “Democrats end up winning

substantial majorities in their core districts my margins like 80-20 or 70-30”

while Republicans can win more districts while having less of an edge as a

majority in the district (Florida 2019). These large Democratic vote margins

can encourage more radical candidates, which overall does more harm to the

party platform in the long run within states, as noted by Andrew

B Hall’s “What Happens When Extremists Win Primaries?” The increased

potentiality of creating more extreme candidates of either party “causes severe

damage to the party’s electoral prospects, … makes the party much more likely

to lose the general election today and … makes the opposing party much more

likely to win two to four years later” (Hall 2015).

Solutions to this issue may involve alleviating partisan gerrymandering of districts in an effort to negate the homogeneity of Democratic voters within a state's districts. One such clear example was Pennsylvania in the 2012 general election, as even though "Democratic candidates for Congress won 51% of the votes state-wide [they] came away with majorities in only 28% of the districts." However, even with a computer program that tried to rectify this imbalance of votes to party seats, these "party blind" plans nevertheless still gave Democrats a disadvantage (G.E.M. 2019). Party polarization seems to not be abating anytime soon but author and Stanford

political scientist Jonathon Rodden did note that suburbs are key to becoming

the possible solution to this clear divide. “In the long run, perhaps the

changing populations and greater mixing of the suburbs may help us overcome some

of the extreme polarization that plagues us today” (Florida 2019).

Works

Cited

Adler, Scott, Jeffery A. Jenkins, and Charles R.

Shipan, The United States Congress, (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company,

2019), 82.

Brown, Patrick, “Why Democrats Lose,” 31 July 2019,

accessed at https://www.city-journal.org/urban-rural-electoral-divide, 15 Oct

2019.

Florida, Richard, “Why Cities Are Less Powerful in

U.S. National Politics,” 26 Sept 2019, accessed at https://www.citylab.com/life/2019/09/jonathan-rodden-why-cities-lose-book-interview-us-politics/598693/,

15 Oct 2019.

G.E.M., "How America’s urban-rural divide shapes

elections," 3 June 2019, accessed at https://www.economist.com/democracy-in-america/2019/06/03/how-americas-urban-rural-divide-shapes-elections,

15 Oct 2019.

Grier, Peter, “The deep roots of America’s rural-urban

political divide,” 26 Dec 2018, accessed at https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/2018/1226/The-deep-roots-of-America-s-rural-urban-political-divide,

15 Oct 2019.

Hall, Andrew B., “What Happens When Extremists Win

Elections?” Feb 2015, accessed at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000641, 15

Oct 2019.

Comments

Post a Comment